Biography

1475 - 1564

"The greater danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark."

- Michelangelo

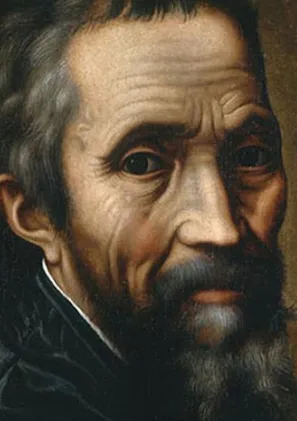

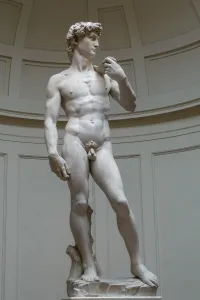

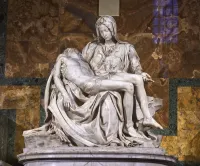

Michelangelo was the first artist to be acknowledged as a genius during his lifetime. He was acclaimed Il Divino (“The Divine One”) for such sculptural masterpieces as The Pieta (1499) and David (1504), the architectural plans for the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica (1547) and, most especially, for his frescos Genesis (1508-1512) and The Last Judgment (1534-1541) on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – collectively the most famous works of art in Christendom. Though he inexplicably burned many of his drawings and papers before he died, Michelangelo left a rich collection of biographical material that includes love sonnets written to many men over the years – in particular, to one Tommaso de’Cavalieri. Because of the seeming incongruity between this evidence and the deep religious convictions associated with his art, most historians have chosen to portray Michelangelo as a tortured celibate – ignoring, until recently, the most obvious characteristic of his life and work: an extraordinary preoccupation with the male form evident in the exquisite quality of the nudes which dominate even in his most sacred work. So absolute was this preoccupation with the male anatomy that many of his few depictions of female nudes are clear adaptations of the muscular male form with breasts appended. For Michelangelo the nude male body personified ultimate beauty and perfection. This same passion for men – which was the driving force behind his poetry – would have become part of shared human culture were it not for his grandnephew who deliberately censored this work by changing the names of the subjects and the gender of the pronouns so they would appear to have been written to women instead of men. The unredacted versions would not be brought to light until 300 years after the artist’s death with the original publication of John Addington Symonds’s The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti. In the 450 years since his passing, historians have firmly defined Michelangelo as a tragic and transcendent artist whose perfection was “beyond human experience.” He died at the age of 89 – with Tommaso de’Cavalieri at his bedside – his genius forever enshrined at the expense of his humanity.

1475 - 1564

"The greater danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark."

- Michelangelo

Michelangelo was the first artist to be acknowledged as a genius during his lifetime. He was acclaimed Il Divino (“The Divine One”) for such sculptural masterpieces as The Pieta (1499) and David (1504), the architectural plans for the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica (1547) and, most especially, for his frescos Genesis (1508-1512) and The Last Judgment (1534-1541) on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – collectively the most famous works of art in Christendom. Though he inexplicably burned many of his drawings and papers before he died, Michelangelo left a rich collection of biographical material that includes love sonnets written to many men over the years – in particular, to one Tommaso de’Cavalieri. Because of the seeming incongruity between this evidence and the deep religious convictions associated with his art, most historians have chosen to portray Michelangelo as a tortured celibate – ignoring, until recently, the most obvious characteristic of his life and work: an extraordinary preoccupation with the male form evident in the exquisite quality of the nudes which dominate even in his most sacred work. So absolute was this preoccupation with the male anatomy that many of his few depictions of female nudes are clear adaptations of the muscular male form with breasts appended. For Michelangelo the nude male body personified ultimate beauty and perfection. This same passion for men – which was the driving force behind his poetry – would have become part of shared human culture were it not for his grandnephew who deliberately censored this work by changing the names of the subjects and the gender of the pronouns so they would appear to have been written to women instead of men. The unredacted versions would not be brought to light until 300 years after the artist’s death with the original publication of John Addington Symonds’s The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti. In the 450 years since his passing, historians have firmly defined Michelangelo as a tragic and transcendent artist whose perfection was “beyond human experience.” He died at the age of 89 – with Tommaso de’Cavalieri at his bedside – his genius forever enshrined at the expense of his humanity.

Demography

Demography

Gender Male

Sexual Orientation Gay

Gender Identity Cisgender

Ethnicity Caucasian/White

Faith Construct Catholic

Nations Affiliated Italy

Era/Epoch Renaissance/Reformation (1300-1700)

Field(s) of Contribution

Architecture

Art

Poet

Commemorations & Honors

Commemoration of 400th Anniversary of Michelangelo's Death (1964)

Michelangelo Among the Members of the Fictional Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1984)

Demography

Gender Male

Sexual Orientation Gay

Gender Identity Cisgender

Ethnicity Caucasian/White

Faith Construct Catholic

Nations Affiliated Italy

Era/Epoch Renaissance/Reformation (1300-1700)

Field(s) of Contribution

Architecture

Art

Poet

Commemorations & Honors

Commemoration of 400th Anniversary of Michelangelo's Death (1964)

Michelangelo Among the Members of the Fictional Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1984)

Resources

Resources

Michelangelo. Michelangelo. The Complete Poems. James Saslow, trans. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991.

Rocke, Michael. Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Saslow, James. Ganymede in the Renaissance. Homosexuality in Art and Society. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986.

Symonds, John Addington. The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti. Nabu Press, 2010.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo

http://www.advocate.com/News/Daily_News/2010/11/15/Michelangelo_Inspired_by_Gay_Bathhouses/

Resources

Michelangelo. Michelangelo. The Complete Poems. James Saslow, trans. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991.

Rocke, Michael. Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Saslow, James. Ganymede in the Renaissance. Homosexuality in Art and Society. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986.

Symonds, John Addington. The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti. Nabu Press, 2010.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo

http://www.advocate.com/News/Daily_News/2010/11/15/Michelangelo_Inspired_by_Gay_Bathhouses/