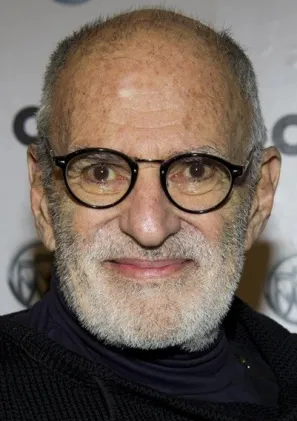

Biography

1935 - 2020

“AIDS was allowed to happen. It is a plague that need not have happened. It is a plague that could have been contained from the very beginning.”

- Larry Kramer

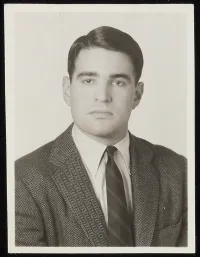

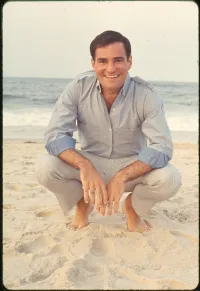

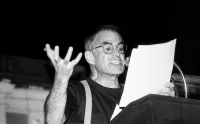

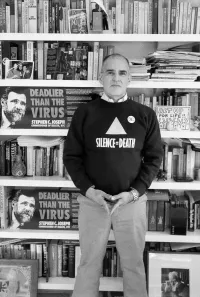

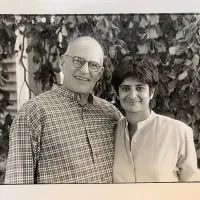

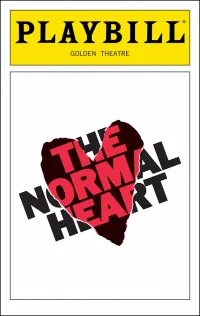

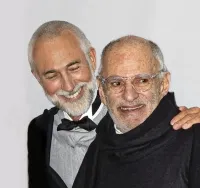

Larry Kramer was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1935 during the height of the Great Depression eight years after his protective older brother and future lawyer Arthur Kramer was born. He enrolled at Yale University in 1953 (the alma mater of his father, brother and two uncles) where he struggled to fit in due to his status as a gay man who had to stay closeted. While in college, Kramer attempted to die by suicide via an aspirin overdose. After that moment, Kramer decided to explore his sexuality, become an LGBTQ+ activist and joined the Yale Glee Club. He graduated with an English degree in 1957 and served in the U.S. Army Reserves for a time. Then Kramer embarked on a career in Hollywood, first as a Columbia Pictures Teletype operator and then in the story department where he was a script doctor. Kramer burst into the public eye when he was nominated for an adapted screenplay Academy Award for Women in Love in 1971. He also became infamous for his controversial and confrontational 1978 novel Faggots the chronicled Manhattan and Fire Island’s gay subculture at that time. This novel caused an uproar in New York’s gay community and was taken off the shelves of the city’s only gay bookstore, the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore, and he was banned from entering a grocery store near his Fire Island home. His whole life changed on the morning of July 3, 1981, when he read a New York Times article about a rare cancer found in 41 gay men. This radicalized Kramer and set him on a course to become one of the United States preeminent HIV/AIDS activists. In 1981, Kramer and other gay men gathered at his apartment to begin this advocate and activist work including founding the first-ever AIDS service organization, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). He was kicked out of the GMHC one year later due to his confrontational style of activism that the other directors didn’t like. Kramer called them “a sad organization of sissies” and in 1983 wrote the "1,112 and Counting" essay for the gay newspaper, the New York Native where he spoke about the acceleration of the disease, condemned gay men’s apathy about AIDS, and accused health officials at every level of government and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center of refusing to address the growing health crisis. He co-founded the direct-action group, ACT UP with activist/filmmaker Vito Russo, in 1987 with a mission to demonstrate in the streets, churches, and other locations to affect positive change. Kramer’s ACT UP activism produced results. After Kramer called the then National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Dr. Anthony Fauci a “murderer” and “an incompetent idiot” due to the federal government’s slow response to AIDS, Fauci agreed to meet with and listen to Kramer and other ACT UP activists. Fauci later said that Kramer’s activism prompted his agency to do more to develop more effective treatments for HIV/AIDS patients. The two eventually became friends. Kramer defended Fauci during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic after he became the face of the White House Task Force and faced attacks from certain pockets of the American public. Following a trip to Europe where Kramer visited the Dachau concentration camp and learned that no one did anything to stop it from opening in 1933, he decided to write the 1981-1984 New York City set The Normal Heart in 1985 to raise awareness of the AIDS crisis so people would rise up and demand that this plague got addressed by government officials and medical professionals in a proper and humane way. Kramer’s other best-known play, the Pulitzer Prize finalist The Destiny of Me (1992) and The Normal Heart had autobiographical elements within them in the character of Ned Weeks that was Kramer’s alter ego. His other written works include the fiction books The American People Volume 1, Search for My Heart (2015) and The American People: Volume 2, The Brutality of Fact (2020), non-fiction books Reports from the Holocaust: The Making of an AIDS Activist (1989, revised 1994) and The Tragedy of Today’s Gays (2005) and various dramas, screenplays, speeches and an article for POZ Magazine in 2000 called “Be Very Afraid.” In 1988, Kramer was diagnosed with HIV and in 2001 he developed liver disease and needed a transplant which he received that year from the University of Pittsburg’s Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute after being turned down by Mount Saini Hospital. Fauci helped Kramer be included in a lifesaving experimental drug trial after his surgery. Although Kramer and his brother had an on and off contentious relationship throughout their lives Arthur gave $1 million to Yale in 2001 to create the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies and his law firm Kramer Levin LLP did numerous pro-bono work for LGBTQ+ causes for many years. In addition to Kramer’s Oscar and Pulitzer Prize nominations; he received two Obie Awards for The Destiny of Me (1993), Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play for The Normal Heart (2011), Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing for a Miniseries, Movie or Dramatic Special for the HBO movie adaptation of The Normal Heart (2014) and posthumously inducted into Stonewall Inn’s National LGBTQ Wall of Honor (2020) among other accolades. Kramer died of pneumonia on May 27, 2020, in his Greenwich Village Manhattan, New York City home with David Webster, his longtime partner (since 1991) and husband (they were married in 2013 in NYU’s Langone Medical Center’s intensive care unit while Kramer recovered from surgery) by his side. At Kramer’s memorial service at the Lucille Lortel Theater in the West Village; luminaries Fauci, HIV/AIDS activist Peter Staley, playwright Tony Kushner, and New Yorker writer Calvin Trillin among others spoke about his life and work and the impact he had on their lives. His memorial booklet was fashioned like the iconic Playbill booklets given to attendees of Broadway productions. After Kramer’s memorial service, Fauci wrote a New York Times op-ed titled, “Anthony Fauci on Larry Kramer and Loving Difficult People,” where he spoke about their tumultuous early encounters in the late 1980s/early 1990s and eventual friendship. At the time of Kramer’s death, he was working on a play about LGBTQ+ people living through three plagues—HIV/AIDS, COVID-19 and the human body’s decline.

1935 - 2020

“AIDS was allowed to happen. It is a plague that need not have happened. It is a plague that could have been contained from the very beginning.”

- Larry Kramer

Larry Kramer was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1935 during the height of the Great Depression eight years after his protective older brother and future lawyer Arthur Kramer was born. He enrolled at Yale University in 1953 (the alma mater of his father, brother and two uncles) where he struggled to fit in due to his status as a gay man who had to stay closeted. While in college, Kramer attempted to die by suicide via an aspirin overdose. After that moment, Kramer decided to explore his sexuality, become an LGBTQ+ activist and joined the Yale Glee Club. He graduated with an English degree in 1957 and served in the U.S. Army Reserves for a time. Then Kramer embarked on a career in Hollywood, first as a Columbia Pictures Teletype operator and then in the story department where he was a script doctor. Kramer burst into the public eye when he was nominated for an adapted screenplay Academy Award for Women in Love in 1971. He also became infamous for his controversial and confrontational 1978 novel Faggots the chronicled Manhattan and Fire Island’s gay subculture at that time. This novel caused an uproar in New York’s gay community and was taken off the shelves of the city’s only gay bookstore, the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookstore, and he was banned from entering a grocery store near his Fire Island home. His whole life changed on the morning of July 3, 1981, when he read a New York Times article about a rare cancer found in 41 gay men. This radicalized Kramer and set him on a course to become one of the United States preeminent HIV/AIDS activists. In 1981, Kramer and other gay men gathered at his apartment to begin this advocate and activist work including founding the first-ever AIDS service organization, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). He was kicked out of the GMHC one year later due to his confrontational style of activism that the other directors didn’t like. Kramer called them “a sad organization of sissies” and in 1983 wrote the "1,112 and Counting" essay for the gay newspaper, the New York Native where he spoke about the acceleration of the disease, condemned gay men’s apathy about AIDS, and accused health officials at every level of government and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center of refusing to address the growing health crisis. He co-founded the direct-action group, ACT UP with activist/filmmaker Vito Russo, in 1987 with a mission to demonstrate in the streets, churches, and other locations to affect positive change. Kramer’s ACT UP activism produced results. After Kramer called the then National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Dr. Anthony Fauci a “murderer” and “an incompetent idiot” due to the federal government’s slow response to AIDS, Fauci agreed to meet with and listen to Kramer and other ACT UP activists. Fauci later said that Kramer’s activism prompted his agency to do more to develop more effective treatments for HIV/AIDS patients. The two eventually became friends. Kramer defended Fauci during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic after he became the face of the White House Task Force and faced attacks from certain pockets of the American public. Following a trip to Europe where Kramer visited the Dachau concentration camp and learned that no one did anything to stop it from opening in 1933, he decided to write the 1981-1984 New York City set The Normal Heart in 1985 to raise awareness of the AIDS crisis so people would rise up and demand that this plague got addressed by government officials and medical professionals in a proper and humane way. Kramer’s other best-known play, the Pulitzer Prize finalist The Destiny of Me (1992) and The Normal Heart had autobiographical elements within them in the character of Ned Weeks that was Kramer’s alter ego. His other written works include the fiction books The American People Volume 1, Search for My Heart (2015) and The American People: Volume 2, The Brutality of Fact (2020), non-fiction books Reports from the Holocaust: The Making of an AIDS Activist (1989, revised 1994) and The Tragedy of Today’s Gays (2005) and various dramas, screenplays, speeches and an article for POZ Magazine in 2000 called “Be Very Afraid.” In 1988, Kramer was diagnosed with HIV and in 2001 he developed liver disease and needed a transplant which he received that year from the University of Pittsburg’s Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute after being turned down by Mount Saini Hospital. Fauci helped Kramer be included in a lifesaving experimental drug trial after his surgery. Although Kramer and his brother had an on and off contentious relationship throughout their lives Arthur gave $1 million to Yale in 2001 to create the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies and his law firm Kramer Levin LLP did numerous pro-bono work for LGBTQ+ causes for many years. In addition to Kramer’s Oscar and Pulitzer Prize nominations; he received two Obie Awards for The Destiny of Me (1993), Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play for The Normal Heart (2011), Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing for a Miniseries, Movie or Dramatic Special for the HBO movie adaptation of The Normal Heart (2014) and posthumously inducted into Stonewall Inn’s National LGBTQ Wall of Honor (2020) among other accolades. Kramer died of pneumonia on May 27, 2020, in his Greenwich Village Manhattan, New York City home with David Webster, his longtime partner (since 1991) and husband (they were married in 2013 in NYU’s Langone Medical Center’s intensive care unit while Kramer recovered from surgery) by his side. At Kramer’s memorial service at the Lucille Lortel Theater in the West Village; luminaries Fauci, HIV/AIDS activist Peter Staley, playwright Tony Kushner, and New Yorker writer Calvin Trillin among others spoke about his life and work and the impact he had on their lives. His memorial booklet was fashioned like the iconic Playbill booklets given to attendees of Broadway productions. After Kramer’s memorial service, Fauci wrote a New York Times op-ed titled, “Anthony Fauci on Larry Kramer and Loving Difficult People,” where he spoke about their tumultuous early encounters in the late 1980s/early 1990s and eventual friendship. At the time of Kramer’s death, he was working on a play about LGBTQ+ people living through three plagues—HIV/AIDS, COVID-19 and the human body’s decline.

Demography

Demography

Gender Male

Sexual Orientation Gay

Gender Identity Cisgender

Ethnicity Caucasian/White Jewish

Faith Construct Judaic

Nations Affiliated United States

Era/Epoch AIDS Era (1980-present) Cold War (1945-1991) Information Age (1970-present) Post-Stonewall Era (1974-1980) Stonewall Era (1969-1974)

Field(s) of Contribution

Advocacy & Activism

Author

Film

Media & Communications

Social Justice

Social Sciences

Television

Theater

US History

Commemorations & Honors

Academy Award Nomination for Adapted Screenplay for Women in Love (1970)

Pulitzer Prize Finalist for The Destiny in Me (1993)

Two-Time Obie Award Winner for The Destiny of Me (1993)

American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature (1996)

Common Cause Public Service Awardee (1996)

Elected to the American Philosophical Society (2005)

Tony Award Winner for Best Revival of a Play for The Normal Heart (2011)

Dartmouth College Montgomery Fellowship Recipient (2012)

PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Award for a Master American Dramatist (2013)

Emmy Award Winner for Outstanding Writing for a Miniseries, Movie or a Dramatic Special for the HBO Movie Adaptation of The Normal Heart (2014)

Gay Men's Health Crisis Inaugural Larry Kramer Activism Awardee (2015)

National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument Inductee (2020)

Demography

Gender Male

Sexual Orientation Gay

Gender Identity Cisgender

Ethnicity Caucasian/White Jewish

Faith Construct Judaic

Nations Affiliated United States

Era/Epoch AIDS Era (1980-present) Cold War (1945-1991) Information Age (1970-present) Post-Stonewall Era (1974-1980) Stonewall Era (1969-1974)

Field(s) of Contribution

Advocacy & Activism

Author

Film

Media & Communications

Social Justice

Social Sciences

Television

Theater

US History

Commemorations & Honors

Academy Award Nomination for Adapted Screenplay for Women in Love (1970)

Pulitzer Prize Finalist for The Destiny in Me (1993)

Two-Time Obie Award Winner for The Destiny of Me (1993)

American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature (1996)

Common Cause Public Service Awardee (1996)

Elected to the American Philosophical Society (2005)

Tony Award Winner for Best Revival of a Play for The Normal Heart (2011)

Dartmouth College Montgomery Fellowship Recipient (2012)

PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Award for a Master American Dramatist (2013)

Emmy Award Winner for Outstanding Writing for a Miniseries, Movie or a Dramatic Special for the HBO Movie Adaptation of The Normal Heart (2014)

Gay Men's Health Crisis Inaugural Larry Kramer Activism Awardee (2015)

National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument Inductee (2020)

Resources

Resources

Kramer, Larry. Reports from the Holocaust: The Making of an AIDS Activist. New York: St. Martins Press, 1989 (revised 1994).

Kramer, Larry. The Tragedy of Today's Gays. London: Tarcher, 2005.

Mass, Lawrence. We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Larry-Kramer

https://www.biography.com/activists/a66965585/laurence-david-kramer

https://www.advocate.com/larry-kramer

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/aids/interviews/kramer.html

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/postscript/the-benevolent-rage-of-larry-kramer

https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2014/art-talk-larry-kramer

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/27/us/larry-kramer-dead.html

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/larry-kramer-playwright-and-aids-activist-dies-at-84

https://playbill.com/article/playwright-and-ardent-aids-activist-larry-kramer-dies-at-84

https://windycitytimes.com/2020/05/27/lgbt-giant-larry-kramer-dies-at-84/

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/28/larry-kramer-obituary

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/27/style/larry-kramer-memorial.html

https://gaycitynews.com/larry-kramer-remembered-love-moving-memorial-service/

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/04/opinion/anthony-fauci-larry-kramer.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/nyregion/coronavirus-larry-kramer-aids.html

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31351-9/fulltext

https://www.poz.com/article/larry-kramer-iconic-aids-activist-remembered-memorial

https://slate.com/human-interest/2020/06/larry-kramer-aids-lgbtq-activism-lessons.html

https://windycitytimes.com/2020/06/02/remembering-a-leader-larry-kramer/

https://windycitytimes.com/2011/05/25/aids-the-angry-heart-of-larry-kramer/

https://windycitytimes.com/2020/05/30/theater-larry-kramer-1935-2020-polemicist-and-playwright/

https://www.villagepreservation.org/village-voices-larry-kramer/

Resources

Kramer, Larry. Reports from the Holocaust: The Making of an AIDS Activist. New York: St. Martins Press, 1989 (revised 1994).

Kramer, Larry. The Tragedy of Today's Gays. London: Tarcher, 2005.

Mass, Lawrence. We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Larry-Kramer

https://www.biography.com/activists/a66965585/laurence-david-kramer

https://www.advocate.com/larry-kramer

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/aids/interviews/kramer.html

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/postscript/the-benevolent-rage-of-larry-kramer

https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2014/art-talk-larry-kramer

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/27/us/larry-kramer-dead.html

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/larry-kramer-playwright-and-aids-activist-dies-at-84

https://playbill.com/article/playwright-and-ardent-aids-activist-larry-kramer-dies-at-84

https://windycitytimes.com/2020/05/27/lgbt-giant-larry-kramer-dies-at-84/

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/28/larry-kramer-obituary

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/27/style/larry-kramer-memorial.html

https://gaycitynews.com/larry-kramer-remembered-love-moving-memorial-service/

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/04/opinion/anthony-fauci-larry-kramer.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/nyregion/coronavirus-larry-kramer-aids.html

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31351-9/fulltext

https://www.poz.com/article/larry-kramer-iconic-aids-activist-remembered-memorial

https://slate.com/human-interest/2020/06/larry-kramer-aids-lgbtq-activism-lessons.html

https://windycitytimes.com/2020/06/02/remembering-a-leader-larry-kramer/

https://windycitytimes.com/2011/05/25/aids-the-angry-heart-of-larry-kramer/

https://windycitytimes.com/2020/05/30/theater-larry-kramer-1935-2020-polemicist-and-playwright/

https://www.villagepreservation.org/village-voices-larry-kramer/