Biography

1882 - 1941

"To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions — there we have none."

- Virginia Woolf

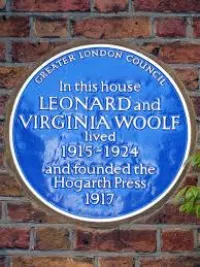

In 1908 Virginia Stephen vowed to “re-form” how the novel was written. Along with Leonard Woolf, whom she married in 1912, the couple began Hogarth Press in 1917, with the goal of bringing to print the best and most original work that came their way. Together they published works by T.S. Eliot, Sigmund Freud, Katherine Mansfield, Gertrude Stein, Vita Sackville-West, and E.M. Forster as well as their own work. Woolf’s first novel was The Voyage Out (1915) followed by Night and Day (1919) and Jacob’s Room (1922). However it was with Mrs. Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) and The Waves (1931) that she established herself as a leading writer of modernism. She developed her innovative techniques – stream of consciousness, interior dialogue, and non-linear narrative – to reveal women’s experience more fully. Though Woolf and her husband shared a dynamic friendship and professional partnership, physical intimacy was not central to their life together. Instead Woolf was romantically involved with a number of women. Her most passionate and renowned relationship was with Vita Sackville-West, for whom she wrote the experimental and semi-biographical novel Orlando (1928), an androgynous tribute to West’s ancestry, illustrated with pictures of West dressed as the title character. During the interwar years the Woolfs were important members of the Bloomsbury Group, a diverse band of intellectuals which included Forster, West, Lytton Strachey, economist John Maynard Keynes, critic Clive Bell, and painter Duncan Grant. A prolific writer, Woolf wrote 15 books, numerous volumes of diaries, letters, and collected essays, and the definitive feminist treatise A Room of One’s Own. Having long suffered from clinical depression, Woolf’s emotional demons eventually overcame her. She drowned herself in the river near her Sussex home in 1941 at the age of 59.

1882 - 1941

"To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions — there we have none."

- Virginia Woolf

In 1908 Virginia Stephen vowed to “re-form” how the novel was written. Along with Leonard Woolf, whom she married in 1912, the couple began Hogarth Press in 1917, with the goal of bringing to print the best and most original work that came their way. Together they published works by T.S. Eliot, Sigmund Freud, Katherine Mansfield, Gertrude Stein, Vita Sackville-West, and E.M. Forster as well as their own work. Woolf’s first novel was The Voyage Out (1915) followed by Night and Day (1919) and Jacob’s Room (1922). However it was with Mrs. Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) and The Waves (1931) that she established herself as a leading writer of modernism. She developed her innovative techniques – stream of consciousness, interior dialogue, and non-linear narrative – to reveal women’s experience more fully. Though Woolf and her husband shared a dynamic friendship and professional partnership, physical intimacy was not central to their life together. Instead Woolf was romantically involved with a number of women. Her most passionate and renowned relationship was with Vita Sackville-West, for whom she wrote the experimental and semi-biographical novel Orlando (1928), an androgynous tribute to West’s ancestry, illustrated with pictures of West dressed as the title character. During the interwar years the Woolfs were important members of the Bloomsbury Group, a diverse band of intellectuals which included Forster, West, Lytton Strachey, economist John Maynard Keynes, critic Clive Bell, and painter Duncan Grant. A prolific writer, Woolf wrote 15 books, numerous volumes of diaries, letters, and collected essays, and the definitive feminist treatise A Room of One’s Own. Having long suffered from clinical depression, Woolf’s emotional demons eventually overcame her. She drowned herself in the river near her Sussex home in 1941 at the age of 59.

Demography

Demography

Gender Female

Sexual Orientation Bisexual

Gender Identity Cisgender

Ethnicity Caucasian/White

Faith Construct Agnostic

Nations Affiliated United Kingdom

Era/Epoch First-wave Feminism (1848-1930)

Field(s) of Contribution

Author

Business

Commemorations & Honors

Busts Erected at Her Homes in Rodmell, Sussex and Tavistock, London

Virginia Woolf Building Opened at Her Alma Mater King's College London Also Includes a Commemorative Plaque (2013)

Inaugural San Francisco Rainbow Honor Walk Honoree (2014)

Google Doodle Commemorating Woolf's 136th Birthday (2018)

Demography

Gender Female

Sexual Orientation Bisexual

Gender Identity Cisgender

Ethnicity Caucasian/White

Faith Construct Agnostic

Nations Affiliated United Kingdom

Era/Epoch First-wave Feminism (1848-1930)

Field(s) of Contribution

Author

Business

Commemorations & Honors

Busts Erected at Her Homes in Rodmell, Sussex and Tavistock, London

Virginia Woolf Building Opened at Her Alma Mater King's College London Also Includes a Commemorative Plaque (2013)

Inaugural San Francisco Rainbow Honor Walk Honoree (2014)

Google Doodle Commemorating Woolf's 136th Birthday (2018)

Resources

Resources

Barrett, Ellen, and Patricia Cramer. Virginia Woolf: Lesbian Readings. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

DeSalvo, Louise A. "Lighting the Cave: The Relationship between Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf." Signs 8.2 (Winter 1982): 195-214.

Hawkes, Ellen. "Woolf's 'Magical Garden of Woman.'" New Feminist Essays on Virginia Woolf. Jane Marcus, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981. 31-60.

Herrmann, Anne. The Dialogic and Difference: "An/Other Woman" in Virginia Woolf and Christa Wolf. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

Jensen, Emily. "Clarissa Dalloway's Respectable Suicide." Virginia Woolf: A Feminist Slant. Jane Marcus, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. 162-179.

Knopp, Sherron E. "'If I saw you would you kiss me?': Sapphism and the Subversiveness of Virginia Woolf's Orlando." Sexual Sameness: Textual Differences in Lesbian and Gay Writing. Joseph Bristow, ed. London: Routledge, 1992. 111-127.

Love, Jean O. "Orlando and Its Genesis: Venturing and Experimenting in Art, Love, and Sex." Virginia Woolf: Revaluation and Continuity. Ralph Freedman, ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. 189-218.

Meese, Elizabeth. "When Virginia Looked at Vita, What Did She See; or Lesbian : Feminist : Woman----What's the Differ(e/a)nce?" Feminist Studies 18.1 (Spring 1992): 99-118.

Raitt, Suzanne. Vita and Virginia: The World and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Rosenman, Ellen Bayuk. "Sexual Identity and A Room of One's Own: 'Secret Economies' in Virginia Woolf's Feminist Discourse." Signs 14.3 (Spring 1989): 634-650.

Sproles, Karyn Z. Desiring Women: The Partnership of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2006.

https://www.vulture.com/2018/10/why-virginia-woolfs-orlando-feels-essential-right-now.html

https://www.autostraddle.com/vita-and-virginia-love-letters-378151/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Woolf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vita_Sackville-West (mentions Woolf)

Resources

Barrett, Ellen, and Patricia Cramer. Virginia Woolf: Lesbian Readings. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

DeSalvo, Louise A. "Lighting the Cave: The Relationship between Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf." Signs 8.2 (Winter 1982): 195-214.

Hawkes, Ellen. "Woolf's 'Magical Garden of Woman.'" New Feminist Essays on Virginia Woolf. Jane Marcus, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981. 31-60.

Herrmann, Anne. The Dialogic and Difference: "An/Other Woman" in Virginia Woolf and Christa Wolf. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

Jensen, Emily. "Clarissa Dalloway's Respectable Suicide." Virginia Woolf: A Feminist Slant. Jane Marcus, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. 162-179.

Knopp, Sherron E. "'If I saw you would you kiss me?': Sapphism and the Subversiveness of Virginia Woolf's Orlando." Sexual Sameness: Textual Differences in Lesbian and Gay Writing. Joseph Bristow, ed. London: Routledge, 1992. 111-127.

Love, Jean O. "Orlando and Its Genesis: Venturing and Experimenting in Art, Love, and Sex." Virginia Woolf: Revaluation and Continuity. Ralph Freedman, ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. 189-218.

Meese, Elizabeth. "When Virginia Looked at Vita, What Did She See; or Lesbian : Feminist : Woman----What's the Differ(e/a)nce?" Feminist Studies 18.1 (Spring 1992): 99-118.

Raitt, Suzanne. Vita and Virginia: The World and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Rosenman, Ellen Bayuk. "Sexual Identity and A Room of One's Own: 'Secret Economies' in Virginia Woolf's Feminist Discourse." Signs 14.3 (Spring 1989): 634-650.

Sproles, Karyn Z. Desiring Women: The Partnership of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2006.

https://www.vulture.com/2018/10/why-virginia-woolfs-orlando-feels-essential-right-now.html

https://www.autostraddle.com/vita-and-virginia-love-letters-378151/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Woolf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vita_Sackville-West (mentions Woolf)